Five years after the first scholarly work was done in this area of study, the University of the West Indies conducted an action research in 1960. The institution responded to a request from some Rastafarians leaders to assist in providing greater understanding of the movement after the violence related to the Back-to-Africa events in 1959. According to Nettleford et al, “the movement is rooted in unemploymentiv and that Marcus Garvey was that prophet that inspired the ideav: and doctrine that Ras Tafari is Messiah returned to earth. They write that the “prophecy was revealed” after the coronation of Haile Selassie in 1930 by four leaders independently.” Of these, Mr. Leonard P. Howell is genuinely regarded as the first to preach the divinity of Rastafari in Kingston”vi. The study argues that “the most successful preacher was undoubtedly L. P. Howell who moved between Port Morant and Kingston until 1940”vii. The1960 Report states that “from 1933 Howell had been preaching violence from 1933” and that Pinnacle was a ganja farmviii. There is no evidence to that supported the theory of four preachers, but this researcher was informed that it was M.G. Smith’s orientation of pluralism that inspired the notionix.

Two years after The 1960 Report, Katrin Norris published the book In Search of Identity in 1962-. H. Orlando Patterson’s novel The Children of Sisyphus, and a short journal article “Rastafari: The Cult of Outcasts”, both published in 1964. Norris, 1962 dedicated a chapter in her book, “The Call of Africa” to the African aspect of the political scene in the 1960, emphasizing the character of Millard Johnson and his resurrection of Marcus Garvey’s people’s Political Party and Sam Brown and black politics. In the article “Rastafari: The Cult Of Outcasts”, the writer describes the “millenarian cult of Rastafari” as “bizarre” and “fantasy” group, that functions as an outlet for “frustration” as opposed to agent for revolutionary changexi. Leonard P. Howell was not mentioned in any of these texts.

This researcher describes the 1970’s as the Golden Period for the study on this topic. Two of the significant sociological studies of the period are: The Rastafarians by Leonard Barrett, 1977 and Millenarian Movements and the Politics of Liberation: The Rastafarians of Jamaica, a PhD study in Sociology conducted in 1977 by Klaus De Albuquerque. Barrett, 1977 provides extensive coverage of Ras Sam Brown in the politics of the 1960’s at the eve of independence. In looking at the wider society, the writer illustrates the consciousness inspired by Marcus Garvey and rooted in a new era of Ethiopianism from George Lisle to Paul Boglexii. The writer describes the movement in terms of “hatred” and “violence”xiii. According to Barrett, 1977 links a brief story of sedition, arrest and trial of Howell as the “first glimpse of the doctrine” that launched the movementxiv. According to the writer Garvey inspired the movement and Howell developed the doctrine. De Albuquerque, 1977 emphasizes the history of religious-political insurrection in the history of Jamaicaxv; also interesting is the story of the influence of Rastafari in the politics of the 1970’s and its association with Michael Manley and the election of 1972xvi. The writer ‘s short but important history of Leonard P. Howell in St. Thomas credits the latter for the creation of a “new awareness”xvii informed by moral justice that began the “minds of men”xviii. The new awareness unleashed a “political awakening”xix. The writer, unlike, the earliest studies, made reasonable use of limited primary and secondary data that uncover the central role of Howell and the emergence of early Rastafari. Howell is characterized beyond the first preacher’s role. It is implied from this study that Howell is a significant thinking person whose ideas penetrated the colonial situation and “awakened” a sleeping majority.

The Lions In Babylon: The Rastafarians in Jamaica As a visionary Movement is an anthropological study and PhD Dissertation by Canadian scholar Carol Yawney in 1971, The Rastafari Brethren of Jamaica published in 1971 by Shelia Kitzinger and Dread: The Rastafarians of Jamaica, by Fr. Joseph Owens published in 1976 were important anthropological studies of Rastafari. The anthropologists, as researchers, immersed themselves into the setting of the problem to gain first hand information in order to examine practices and to create meanings. Yawney, 1971 conducted the research in Kingston. She worked primarily with Mortimo Planno and the politics of repatriationxx. Howell was no where in the setting. Kitzinger, 1971 who visited among urban and rural Rastas from the Nyabinghi sect. In her opening remarks she defines the Rastafarians as a “social problem for Jamaica ever since 1933” and linked this claim to the idea about Howell’s selling of Selassie’s picture as passports to Ethiopia”xxi.

In 1976 a Roman Catholic priest and social worker Father Owens published his anthropological study in which he argues that Rastafarian theology is radically different from Christianity and that it consistently promoted “race consciousness” in Jamaicaxxii. The Rastafari view of the Bible, he argues, generated a critique of the very foundation of Christian civilization, capitalism and imperialism, promoting a new anti-imperialist trend in the wider Caribbeanxxiii. Like some of the earlier studies on Rastafari, he identified Garvey as a prophet of the movementxxiv. However, making limited use of secondary sources, newspaper articles, he locates the origin of the movement in St, Thomas where Howell in 1933 that Haile Selassie “is Messiah” returned to earthxxv. In making sense of Howell’s 1934 sedition trial, he writes, “Howell’s trial in 1934 set the precedence by which Rastas would later follow”xxvi. In spite of his earlier charge that Garvey is a prophet of the movement, he states with authority that Howell is, indeed, “the Rastafari prophet”xxvii. This writer affords Howell a central role in the emergence of Rastafari and well as opening the door for deeper studies to explore Howell’s contribution to the school of the idea of Ethiopianism.

The social anthropological studies of Barry Chevannes have contributed an array of insightful perspectives to Rastafari scholarship by way of three major published and unpublished works. His major works are: Jamaica Lower Class Religions: Struggles Against Oppression, Masters’ Thesis, University of the West Indies, 1977; Social and Ideological Origins of the Rastafari Movement in Jamaica”, PhD Dissertation, Columbia University, 1989; and Rastafari: Roots and Ideology published in 1994. Chevannes, 1977 introduces the framework of exploring the idea of Rastafari as a renewal of the Myal/Revivalist traditions as foundation of the movement. He argues that Rastafari emerged out of the “Africanization” of the Myal/Revival traditionxxviii. Against this background he lionizes Bedward for the “Africanization” of the older traditions and Rev. Claudius Henry for “his prophetic leadership of the Rastafari movement”xxix. Marcus Garvey is elevated to prophetic status for his “look to Africa for the crowning of a Black King” dramatic statementxxx and he declares also Robert Hindsxxxi among his panoply of prophets that inspired early Rastafari. It is important to note the important background information on Howell and his New York experience and his relationship with Marxist and radical Pan Africanist, George Padmorexxxii. In a similar voice to that of The 1960 Report by Nettleford et al, 1960, Chevannes, 1989 informs “that Howell is universally credited for being one of if not the first preacher of Rastafari”xxxiii. The writer identifies several prophets of the movement and defines Howell as the first preacher. He suggests also that he was reliably informed that Howell selected St. Thomas to establish “his community of followers” due to the tradition of “anti-colonial resistance”xxxiv of the parish. This tells us that Howell was a man with an extra-ordinary understanding of history. While Howell is characterized as a ganja farmerxxxv the writer notes how his leadership qualities at Pinnacle inspired new developments in important social and cultural formations.

“The Ancient Of Day Seated Black: Eldership, Oral Traditions and Rituals is an anthropological PhD Dissertation by John Paul Homiak, 1989, is a reflection of present day Rastafari through the voices of leadership-the Elders of the Nyabinghi Rastafari. Rastafari, he suggests, emerged as an anti- colonialist and “anti-imperialistxxxvi response to European oppression and slavery; and that nationally the political influence of Howell set off a tensionxxxvii between the lower classes and the colonial leadership. The prophet of the movement is identified as Marcus Garveyxxxviii , however he notes that the “new Ethiopian religion emerged out of Howell’s manifestations that began in April 1933; and that Howell’s preaching “clearly formed a corpus of ideas from which others drew and elaborated upon”xxxix. It is this “act”, he writes, that led to “a Rasta wakening worldwide” guided by the new philosophical center of power described “as black supremacy…. the crux of Rasta eschatology”xl. The Nyabinghi movement has its unique basis from which it emerged and it is not surprising that interviews from this group consistently points to Garvey as the prophet of the movement. Homiak, 1989 complimented his interviews with the use of primary and secondary archival materials from which he was able to illustrate Howell’s “corpus of ideas” became the basis for the doctrine of Rastafari.

Post, 1969 looks at “The Politics of Protest in Jamaica, 1938: Some Problems of Analysis and Conceptualization”, and his 1970 “The Bible as Ideology: Ethiopianism in Jamaica, 1930-38” and the books Arise Ye Starvelings and Strike the Iron published in 1978 and 1981 respectively. Post 1969 looks at the background of the 1938 uprisings beginning from March to June 1938 neglecting important events from December 27, 1937 to early January 1938. In an incisive analysis, he illustrates the leading characters and the masses in the radical developments leading up to 1938xli.Post, 1969 discusses the weakness of using Marxism to describe and analyze the activities and events related to the colonial situation. Like some previous studies he declares Garvey as prophet but notes that it was the poorest and most exploited”xlii who were attracted to Howell’s preachingxliii; and that “though Howell went far doctrinally he did not build an organisational form”xliv. Strength of this study is the writer’s portrayal of Howell’s mission in St. Thomas, not in terms of the manifestation of the prophecy but how it activated the parish in a scene of vibrant struggles. The writer argues that Howell had a doctrine and a following but due to no organisational form, he and early Rastas did not contribute to the struggles of 1938.

Contrary to Ken Post studies, Carnegie, 1973 made an inference of the role of the early Rastafari in the political activities of St. Thomasxlv that culminated into the January 1938 activities at Serge Island sugar estatesxlvi. The writer notes that these groups, leaders and functions took place outside of “the sphere of the colonial government”xlvii. In articulating his understanding of the emergence of the idea of Rastafari, the writer shows Howell’s early missionary role and his clashes with the police and that there is a philosophy that is associated with this movement that is “distinctly unorthodox (having) some educated men behind it”xlviii. This story provides account of Howell’s conflict with the police and the critical recognition that in early January 1938 the was a massive strike and confrontation with an “army” of police from Kingston at Serge Island sugar factory in Seaforth, St. Thomas, “the parish in the center of the Rastafari activity”xlix. Howell is defined in terms of an intelligent person with a history of conflicts against the colonial authority and that his influence may have been important in the January 1938 activities at Serge Island, Seaforth St. Thomas..

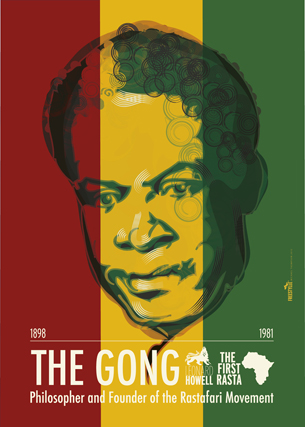

Hill, 1981 is a historical study of distinction because of its “seminal nature” regarding a full length study of Howell as the central character and prophet of early Rastafaril. Leonard P. Howell, according to the writer requires special attention in this study due to his leadership quality in the presentation of him self as ‘Ambassador’ and ‘President General’ of the Kings of King Mission and his prophetic role in the ‘revelation’ of prophecy of the divinity of Ras Tafarili. The writer illustrates Howell’s revelation of prophecy from Trinityville to Port Morant in St. Thomas as “systematic statements of the doctrine; and provides graphic details of the meetings, speeches, fliers bearing his message and a picture of Haile Selassie and the role of the planter and the police, who described Howell’s lectures as ‘seditious’ in naturelii. It is important, also, to note the political impact of The Promised Key on the basis of report by a retired Resident Magistrate who “was worried of the political threat of Rastafari; and so too was the planter Major Cawes of Trinityville, who declared that the book was” dangerous because of the bitter hatred it stirred among certain strata of the lower class in Jamaica”liii. The writer concludes that “these reports point to the very real likelihood that Rastafarian millenarian ideology functioned as an active catalyst in the developing of the popular consciousness that led to the labour uprisings of 1938”liv. The writer highlights Howell’s founding and prophetic role and also an articulation of his activities and political influence in St. Thomas.

The most extensive study on the Rastafari movement was conducted by Frantz Jan Van Dijk, 1993 looking at the rise of Garvey and the UNIA and role in the process of resistance and changelv. Central to his study is the role of prophets and prophecy. In looking at the period from 1930 to 1939 he provides a detailed account of Howell’s mission to St. Thomas. Relying on newspaper articles the writer develops a sterling portrait of Howell, his meetings in St. Thomas and the revelation of prophecylvi; and how the nature of the ‘seditious utterances’ led to Howell’s arrest. The study gives excellent details of the arrest and triallvii. It places Howell as the central character in the story of the emergence of early Rastafari; it illustrates the radical nature of the thinking of early Rastafari, its global reachlviii and influence on the politics of Jamaica during the 1960 and 1970’slix. The lessons from this study points the political influence of the idea of early Rastafari and by extension the political qualities of Howell’s thinking that informed the emergence of the idea.

I have this hunch that in The First Rasta Lee, 2003, may have been on the hunt for the source of Bob Marley’s music when she encountered Leonard P. Howell. This book is very strong in providing personal details on Howell, his life at home and some influence abroad that may have influenced Howell development of his Ethiopianist perspectives, his “Marxist animosities”, his mission to St. Thomas and exodus Pinnaclelx. She portrays Howell as a well dressed character who was fond of women. Her graphic illustration of the size of his fiery sermons and how they provoked serious responses for the colonial elite in Port Morant led to his subsequent arrest and triallxi was instructive. So to we her account of the scene at Howell’s trial inside and outside of the Morant Bay Court House, the size of the crowd, and the prophet’s articulation of his defence for sedition. In looking at an important development in 1938, she asserts that Howell influenced by his “Marxist animosities” by way of his association with Padmore and his reading of The Negro Workerlxii, guided his association with the January 5, 1938 strike and resistance of 1,500 labourers with an expanded police force “at Serge Island, a plantation between Trinityville and Seaforth”, into Rasta territory, and how this event “subsequently transformed the old colonial system”lxiii. The writer charges that Howell made a significant contribution to the politics of de-colonization process in Jamaica. This idea contends with the thinking that the early Rastafari made no contributions to the anti-colonial struggles that culminated in 1938. This book raises also, an issue that shows the influence at the community level in Seaforth, one of the main centres of Rasta activity in St. Thomas.

Bogues, 2003 in Black Heretics, Black Prophets: Radical Black Intellectuals provides a new approach to Howell and the early movement in his conceptualizes the thinking of Rastafari into the “politics of Jah” and “redemptive politics”lxiv. In looking at Howell’s anti-colonial political quality, he argues that Howell created a “symbolic world” to displace the “Anglo-Saxon’s Kingdom with another King and Kingdomlxv. The writer pays careful attention to the role of prophets in prophecy and notes that Howell was deliberate in what he was doing in pioneering the redemptive politics of Jah. This charge was justified by the writer in his analysis of Howell’s thinking and foundational doctrine and illustrate three important moves by the prophet/philosopher: firstly, his thinking was located outside mainstream politics; secondly advance in the political language Haile Selassie and the ‘divinity of Kings’ that brought out the conflict with ‘domesticated Christianity and the colonial situation; and thirdly Howell’s rejection of Christianity is “idolatry” and that black people were worshiping the wrong God”lxvi. This latter indicates also, Howell’s fundamental departure from the traditional thinking in Ethiopianism. The writer shows that at his trial in 1934, Leonard P. Howell not only advanced a new political thinking, but set forth the “early enunciations of Rastafari theology….following a stream of black radical thinking which centered on Africa”lxvii. Howell is defined in prophetic and philosophical proportion.

The earlier studies on Rastafari neglected or provided limited information on the founding thinker of the idea that Rastafari is Messiah returned to earth. Howell has been characterised as a violent person, a ganja farmer and the “first preacher” of Rastafari. Due to limitation of some of the “oral history” studies, Marcus Garvey, in spite of his rejection of the movement, has been identified as prophet of early Rastafari. Some studies provide mixed results by declaring Garvey prophet and Howell “first preacher”. The following researchers: Hill, 1981, Bogues, 2003 and Lee, 2000 locate Howell as the central character in the story of early Rastafari as prophet and philosopher. These writers have dispelled the long held misconception of Garvey’s role a prophet of early Rastafari. Lee, 2000 went further she declared Howell an anti-colonial champion against the background of Howell’s anti- colonial and anti-imperialist political influence in St. Thomas. Indeed Howell is one of the finest organic scholars in the history of Jamaica and the most influential advocate of black consciousness among the lower classes: the cane cutters, the cane loaders, the unemployed, and the marginalized. Today, what began as a rural-based politic-religious movement that has proliferated ‘fragments’ of a new philosophy all over the world.

In concluding, it is important for the clear illustration of the contribution of Howell and early Rastafari in the Jamaican and global society. Some studies have illustrated the influence of Rastafari in the politics of the 1960’s and 1970’s in Jamaica and also its political influence in the Eastern Caribbean in the 1970’s as well as its expansion into the United States of America, then to England and finally to its homeland Africa. It is also important to note the progressive influence of the Rastafari inspired music from Peter Tosh and Bob Marley among African Liberation movements and fighters in Southern Africa during the 1970’s.